Erdoğan’s recent economic record does not look great. From record-level inflation (50% according to the official figures), to a youth unemployment rate of 20%, to the recent fall-out from the earthquake response that revealed the scale of corruption and mismanagement in the construction industry that the Erdoğan regime is entangled in, there did not seem much for Erdoğan to base his re-election campaign on.

Yet, he continues to garner the popular support of around half of the Turkish electorate, winning the May 29, 2023 presidential election run off with an estimated 52.14% of the votes. Even accounting for alleged – and quite likely – fraud and vote rigging that is a remarkable achievement. How can we explain Erdoğan's enduring popularity amongst the significant segments of the voter public who are surely impacted by the current economic and social crises?

One part of the answer is that Erdogan managed to galvanise supporters with messaging about his ‘great achievements’ in science and tech. But this message may have been a lot less effective had it not been for another underlying transformation he has orchestrated over the past 20 years, namely the transformation of the Turkish media system.

One key insight from a recent research project on populism that uses the social network analysis (SNA) technique is that contrary to what we might expect from historical experience with totalitarian regimes, modern-day right-wing authoritarian leaders do not strive for a complete Gleichschaltung of the media. Rather, the analysis of media ownership hints at the fact that the regime tolerates some dissenting voices, whilst making sure the government’s voice is disproportionately heard and oppositional voices are marginalised.

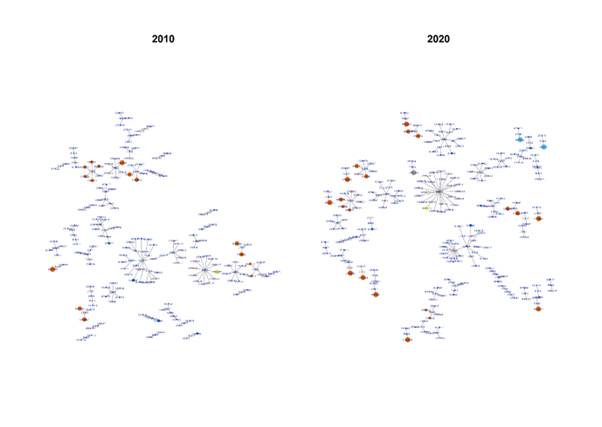

This effect happens when the ownership network shows centre-periphery structure of media ownership, which suggests that messages emanating from the government-controlled centre of the network are ‘louder’ compared to voices emanating from the periphery where oppositional voices are increasingly located. The figure below graphically represents the changing media ownership network structures in Turkey and indicates such core periphery structures.

Turkish media ownership network 2010 and 2020

Erdoğan's media strategy consisted of orchestrating transfers of ownership of established media outlets from old media-elites to the new media elites that have clientelist relationship with Erdoğan's regime. Whilst not abolishing the private media market, the new structure erodes competition between media groups and among journalists. Almost all big players in the media market are comprised of pro-Erdoğan firms. Such a market provides ample opportunities for Erdoğan's truth regime to be told and retold over and over through different outlets and arguably through different styles adapted to the audience of each outlet all of which serve for Erdoğanism and its truth regime.

Turkuvaz Medya Group illustrates the strategy of creating new media owners. Turkuvaz Medya Group is one of the biggest pro-Erdoğan media conglomerates, , owned by Kalyon Holdings. It, possess 60 media outlets including the popular television channels such as ATV and A Haber, and popular dailies such as Sabah. According to recent research, these outlets were not only amongst the most popular news resources for Erdoğan supporters, but they were also amongst the most propagandistic ones serving Erdoğanism during 2018 Presidential election in which Erdoğan won once again the majority of the votes. Kalyon entered the media market by taking over the major media outlets in the country in 2013, when Erdoğan had accelerated his project of redesign of the media market through ownership changes.

Yet, not all oppositional media outlet are brought under control by owners close to Erdoğan. This strategy of ‘managed pluralism’ in the sphere of the media is in line with what scholars of modern authoritarianism have found in the electoral sphere: Modern autocrats do not seek to completely stomp out any opposition. Rather, they seem to be willing to tolerate some opposition, leading to a so-called competitive authoritarianism.

There is a reason for this relative tolerance of dissent. Modern-day right-wing populist rhetoric is based on the ‘us versus them’ discourse, which by necessity requires an enemy. Therefore, opposing voices are not completely silenced, but the ownership of media companies is used to make sure they remain marginal. This makes the populist ‘us versus them’ discourse more effective.

Indeed, media outlets close to the Erdoğan regime constantly disseminate the polarising narrative that Erdoğan's supporters are presented as the real, pure, good Muslims and patriotic Turks and all oppositional groups – including journalists – are represented as enemy, terrorists, and infidels. The co-existence of pro-Erdoğan media outlets and oppositional ones in the media market, helps give this narrative substance. Indeed, contrary to historical cases of totalitarian regimes, modern-day right-wing populists’ ‘competitive authoritarianism’ and the related ‘us versus them’ strategy makes opposition and dissent useful – indeed important – for regime maintenance. When the mediated narrative is organised to create a war-like friend and enemy situation, the destabilising and unpopular issues such as inflation, unemployment or corruption and mismanagement may become much less important.

Erdoğan may not ‘love’ his enemies, but he most definitely needs them to stay in power. In network terms, echo chambers that spread the regimes message far and wide and increase the resonance of the official voice, while dissent is confined to the periphery of the network, is a better tool to square popular support and control than an outright elimination of dissent.